In a recent interview with The Telegraph Newspaper, the Secretary for Work and Pensions, Mel Stride, shared his opinion that “mental health culture has gone too far”. But what does he mean by ‘mental health culture’? And is what he is saying true?

The MP for Central Devon said that “There is a real risk now that we are labelling the normal ups and downs of human life as medical conditions which then actually serve to hold people back and, ultimately, drive up the benefit bill. [ ] If they go to the doctor and say ‘I’m feeling rather down and bluesy’, the doctor will give them on average about seven minutes and then, on 94 per cent of occasions, they will be signed off as not fit to carry out any work whatsoever.”

The facts

In 2022 the number of people being signed off work due to sickness or injury rose by 2.6% from the previous year (Figures from the ONS). The rate of sickness absence from work is now at the highest level since 2004.

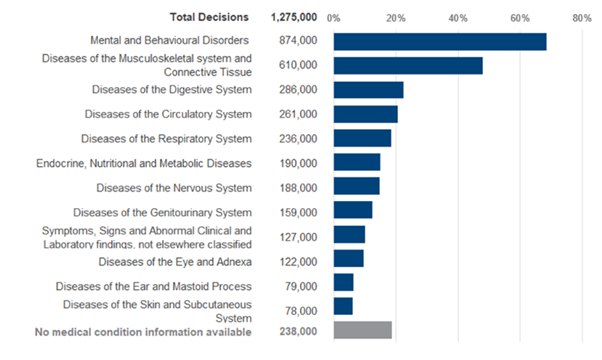

Figures from the Department of Work and Pensions show that the number of people who are claiming Universal Credit, or who have been classified as unable to work, are more likely to list a mental or behavioural disorder as one of the reasons.

Work Capability Assessment Decisions January to November 2023:

However, it should be noted that mental health is usually only one of many reasons recorded when someone is assessed as being unable to work. In reality, research shows us that comorbidities (having two or more diseases or medical conditions) between physical and mental health problems are common.

For example, research from MQ has shown a link between hypermobility and anxiety, meaning that on the above chart someone may be recorded in both the Mental and Behavioural Disorders category and the Diseases of the Musculoskeletal system and Connective Tissue category.

Additionally, MQ research has also shown a link between Cardio-vascular disease and depression and that people who were hospitalised with COVID-19 are more likely to have a diagnosis of depression or an anxiety disorder than the general population.

This means that the figures being shared in the press that ‘almost half of working-age adults with a disability now cite mental health as a cause’ is misleading. Mental illness or mental distress is a cause, as in one of possibly many – not always the sole course of disability.

As is usually the case when it comes to our mental health, nuance is important.

The number of people not in work is only one measure of the growing epidemic of mental illness and mental distress. The demand for services has grown significantly and mental health care providers are becoming overwhelmed.

Referrals to Children and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS) has risen by 353% since 2016, whilst people of all ages are waiting far too long for treatment from a diminished and overburdened workforce.

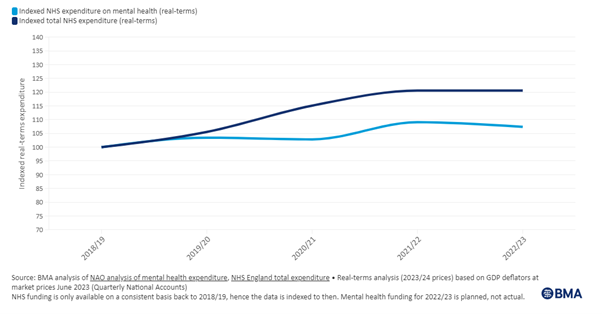

Despite an increase in the overall budget for the NHS, real terms expenditure on mental health care has remained relatively flat.

Nil Güzelgün, of the mental health charity Mind, said the data “highlights the acute need for mental health support”, citing the 1.9 million people on waiting lists for NHS mental health treatment.

“People would love to work if they had access to the mental health support they need but that support just isn’t there,” she said. “People need to be offered tailored support from experts if they are to return to work, not threats of losing what little money they currently have to live on.”

Nil Güzelgün, Policy & Campaigns Manager Mind

So is there a ‘mental health culture?’

The idea that a large portion of the population are ‘feeling a bit bluesy’ and asking to be signed off work is not supported by the evidence.

The DWP’s own website states that claimants of universal credit often have complex health issues which affect their ability to work.

“It's disappointing to hear the comments from the Minister referring to Mental Health as "a culture" as if the thousands of individuals suffering from a mental illness have chosen to be in that position.”

Says Lea Milligan, CEO of MQ Mental Health Research.

“That being said, there is a difference between the normal experiences of life that result in sadness and negative emotions and a diagnosis of common mental disorders (anxiety or depression) or serious mental illness (psychosis). With the right support networks these instances of normal sadness and distress should build resilience and help to develop coping skills for later life. At the same time, however, we have seen a continued increase in the number of eating disorder referrals, downward pressure on the mental health of the most vulnerable due to the cost of living crisis and a continued increase in drug-related deaths linked to addiction. All pointing to a worsening mental health at the serious end of the spectrum.

“Destigmatisation is a net positive - it allows us to help more people and to save lives and shouldn't be impeded by dragging mental health into a culture war mindset. Of all global spending into health research, only 7.4% is invested into mental health research. 26 times more gets invested into cancer research than research into all mental health conditions. That means that when it comes to eating disorders, anxiety disorders, major depressive disorders, psychosis and other conditions there is a risk that people will turn to social media or other less than trusted sources for answers,. Which makes people vulnerable to misinformation and may lead them to self-diagnose. This is exacerbated by the lack of investment in care services and long waiting lists to see medical professionals.”

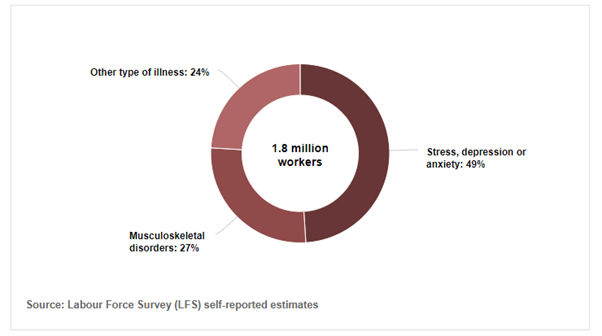

Increasingly, work itself is being recognised as a significant driver of mental illness. Working conditions, stress levels and even the working environment can have a huge impact on mental health, which in turn can impact performance.

A report by the Royal College of Psychiatrists found that 1 in 6.8 people experienced mental health problems in the workplace. Whilst figures from the Health and Safety Executive found that stress, depression, and anxiety attributed to the workplace illness accounted for almost half of all work related illnesses:

Research by MQ, Peopleful, and the Workwell Research Centre at Northwest University found that 1 in 5 employees in the UK are at high risk of burnout, with a further 22% showing signs of stress related ill-health.

“It’s disappointing to see the Secretary of State for Work and Pensions diminish and misrepresent people with mental illness. This is not simply a ‘culture’ that will go away on its own. People are not pretending to be sick, they really are sick.”

Dr Lade Smith CBE, President of the Royal College of Psychiatrists

“There has been a significant increase in poverty, deprivation, housing insecurity and homelessness, loneliness and isolation over the last 15 years and these issues are all associated with depression and anxiety. It is therefore not surprising that we have seen a dramatic rise in people struggling with mental illness, including those who are at risk of self-harm and suicide.

“The Government’s plan to ratchet up sanctioning people with mental illness for not working is unlikely to work – it isn’t working now. These proposals are likely to make people feel worse due to the hardship and debt they will face, which will ultimately cost the NHS and the taxpayer far more in the long run.

“We are dealing with serious illnesses that affect the lives of millions of people, yet many can be prevented and treated effectively with timely access to mental healthcare services.

“There are better ways of supporting people with mental illness to live healthy and productive lives, that are likely to be more successful. For example, the Individual Placement Support programme provides tailored help for people with severe mental illness as they try to secure appropriate work. They should make these types of supportive services more available to all those with mental illness.

“With the right resources, mental health services could support people before they become too unwell to work. I sincerely hope Mel Stride will reconsider his approach.”

So what can be done to reduce the benefit burden?

If the Secretary for Work and Pensions is keen to reduce the number of people out of work due to ill-health, and therefore the benefits spend, evidence has shown that preventing people from becoming sick is more cost-effective than sanctioning people who are already struggling.

More than £2 billion is spent annually on social care for people with mental health problems, with the wider cost being estimated at over £117.9 billion across the UK through lost productivity and informal care costs. Mental Health problems also add considerably to education, criminal and justice systems workloads.

Investing in preventing ill-health, such as by improving early intervention measures, shortening waiting lists, raising living standards and encouraging positive employer workplace practices have all been shown to help reduce the risk of people reaching a crisis point with their mental health.

Early intervention versus crisis intervention for Psychosis alone could save the NHS over £33.5 million each year and shave £63 million off the societal cost of illness.

“Early Intervention Services are recommended in the NHS because of evidence gathered and analysed in a research setting that shows that these services improve outcomes for patients and save money. We have now shown that each person treated in an early intervention service is twice as likely to become employed and 50% more likely to go into stable housing, compared to people with early psychosis who are treated in other services. People in early intervention services also spend less time in hospital, which is good news for them, and also saves the NHS money.”

Professor Belinda Lennox, Oxford Health NHS Foundation Trust

A 2014 report by the LSE and Rethink Mental Illness found that early intervention could equal a net saving of £7,972 per person over four years. Over a ten-year period £15 in costs could be saved for every £1 invested in Early Intervention.

MQ has consistently called on the Government to do more to prevent mental illnesses where possible.

Last year MQ joined calls from 35 mental health organisations for all political parties to prioritise prevention, equality and support in the Mentally Healthier Nations manifesto.

This was in addition to our Cost-of-living report which called for a reshaping of economic and social policies to tackle the underlaying cause of inequalities.

The Gone Too Soon roadmap laid out actionable steps that the government could take to reduce the premature mortality that is associated with serious mental illnesses.

Most recently, MQ contributed to an All-Party Parliamentary Group report that called for a population-wide public health strategy to deal with Adverse Childhood Experiences and reduce the ‘trauma trap’.

All of the above reports, papers and roadmaps are evidence based and make it clear the actions government can take to reduce the burden of mental ill-health.

Dealing with mental illnesses is complex and difficult, but its important for policy makers to remember that these are individuals whose lives are being impacted, not lines on a spreadsheet that make up a financial bottom line.